USS Illinois (BB-65)

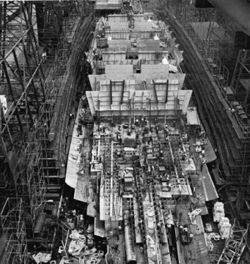

USS Illinois in July 1945, just weeks before construction was canceled |

|

| Career (US) | |

|---|---|

| Ordered: | 9 September 1940 |

| Builder: | Philadelphia Naval Shipyard |

| Laid down: | 15 January 1945 |

| Launched: | Canceled prior to launch |

| Struck: | 12 August 1945 |

| Fate: | Dismantled on builder's ways September 1958 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Iowa-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 45,000 tons (planned) |

| Length: | 887 ft 3 in (270.43 m) (planned) |

| Beam: | 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) (planned) |

| Speed: | 33 kn (38 mph; 61 km/h) (planned) |

| Complement: | 151 officers, 2,637 enlisted (planned) |

| Armament: | (planned): 9 × 16 in (410 mm)/50 cal Mark 7 guns 10 × 5 in (130 mm)/38 cal Mark 12 guns 80 × 40 mm/56 cal anti-aircraft guns 49 × 20 mm/70 cal anti-aircraft guns |

| Armor: | Belt: 12.1 in (310 mm) Bulkheads: 11.3 in (290 mm) Barbettes: 11.6 to 17.3 in (290 to 440 mm) Turrets: 19.7 in (500 mm) Decks: 7.5 in (190 mm) |

USS[A 1] Illinois (BB-65) was to be the fifth Iowa-class battleship constructed for the United States Navy and was the fourth ship to be named in honor of the 21st US state.

Hull BB-65 was originally to be the first ship of the Montana-class battleships, but changes during World War II resulted in her being reordered as an Iowa-class battleship. Adherence to the Iowa-class layout rather than the Montana-class layout allowed BB-65 to gain eight knots in speed, carry more 20 mm and 40 mm anti-aircraft guns, and transit the locks of the Panama Canal; however, the move away from the Montana-class layout left BB-65 with a reduction in the heavier armaments and without the additional armor that were to have been added to BB-65 during her time on the drawing board as USS Montana.

Like her sister ship Kentucky, Illinois was still under construction at the end of World War II. Her construction was canceled in August 1945, but her hull remained until 1958 when it was broken up.

Contents |

Design

The passage of the Second Vinson Act in 1938 had cleared the way for construction of the four South Dakota-class battleships and the first two Iowa class fast battleships (those with the hull numbers BB-61 and BB-62).[1] The latter four battleships of the class, those designated with the hull numbers BB-63, BB-64, BB-65, and BB-66 were not cleared for construction until 1940,[1] and at the time BB-65 and BB-66 were intended to be the first ships of the Montana-class.[2]

Originally, BB-65 was to be the United States Navy's counter to the Empire of Japan's Yamato-class battleships, whose construction at the time was known to the highest ranking members of the United States Navy, along with the rumors that Yamato and Musashi were carrying guns of up to 18 in (457 mm). To combat this, the United States Navy began designing a 58,000 ton ship with an intended armament of twelve 16 in (406 mm) guns. This battleship took shape in the mid-1930s as USS Montana, the lead ship of her class of dreadnought battleships. She would have fielded three more 16 in (406 mm) guns than those mounted aboard the Iowa-class, a more powerful secondary battery of 5 in (130 mm)/54 caliber Mark 45 dual purpose mounts,[3] an increase in armor that was to enable Montana to withstand the effects of the 16 in (410 mm) guns and the 2,700 lb (1,200 kg) ammunition she and her Iowa-class sisters were to carry.

The increase in Montana’s firepower and armor came at the expense of her speed and her Panamax capabilities, but the latter issue was to be resolved through the construction of a third, much wider set of locks at the Panama Canal. As the situation in Europe deteriorated in the late-1930s, the USA began to be concerned once more about its ability to move warships between the oceans. The largest US battleships were already so large as to have problems with the canal locks; and there were concerns about the locks being put out of action by enemy bombing. In 1939, to address these concerns, construction began on a new set of locks for the canal that could carry the larger warships which the US had either under construction or planned for future construction.[4] These locks which would have enabled Montana to transit between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans without the need to sail around the tip of South America.[5] As USS Montana, BB-65 would have been the only battleship class commissioned by the US to approach the Empire of Japan's Yamato-class battleships on the basis of armor, armament, and tonnage.[6][7]

By 1942 the United States Navy shifted its building focus from battleships to aircraft carriers after the successes of carrier combat in both the Battle of Coral Sea, and to a greater extent, the Battle of Midway.[8] As a result the construction of the US fleet of Essex-class aircraft carriers had been given the highest priority for completion in the US shipyards by the US Navy.[7] The Essex-class carriers were proving vital to the war effort by enabling the Allies to gain and maintain air supremacy in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, and were rapidly becoming the principal striking arm of the United States Navy in the ongoing effort to defeat the Empire of Japan.[9] Accordingly, the United States accepted shortcomings in the armor for their North Carolina-class battleships, South Dakota-class, and Iowa class battleships in favor of additional speed, which enabled these battleship classes to steam at a comparable speed with the Essex-class and provide the carriers with the maximum amount of anti-aircraft protection.[9]

Development

When BB-65 was redesignated an Iowa-class battleship, she was assigned the name Illinois and reconfigured to adhere to the "fast battleship" designs planned in 1938 by the Preliminary Design Branch at the Bureau of Construction and Repair.[10][A 2] Her funding was authorized via the passage of the Two Ocean Navy bill through the United States Congress in 1940,[A 3] and she would now be the fifth Iowa class battleship built for the United States Navy.[10][11]

Like her Iowa-class sisters, Illinois was to cost US $125 million[12] and take approximately 30 to 40 months to complete.[13] She would be tasked primarily with the defense of the US fleet of Essex-class aircraft carriers. In adherence with the Iowa-class design, Illinois would have a maximum beam of 108 ft (33 m) and a waterline length of 860 ft (260 m), permitting a maximum speed of 34.9 knots (64.6 km/h). The Navy also called for the class to have a lengthened forecastle, amid-ship, and a bulbous bow, which would increase her speed to 35 knots.[1]

Like Kentucky, Illinois differed from her earlier sisters in that her design called for an all-welded construction, which would have saved weight and increased strength over a combination riveted/welded hull used on the four completed Iowa-class ships. Engineers considered retaining the original Montana-class armor for added torpedo and naval mine protection because the newer scheme would have improved Illinois’ armor protection by as much as 20%.[14] This was rejected due to time constraints and Illinois was built with an Iowa-class hull design.[1] Funding for the battleship was provided in part by "King Neptune", a Hereford swine auctioned across the state of Illinois as a fund raiser, and ultimately helped raise $19 million in war bonds[15] (equivalent to about $200 million in 2007 adjusted dollars).[16]

Scrapping

Illinois's keel was laid down at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 6 December 1942, but her construction was canceled on 11 August 1945, when she was about 22% complete.[11] She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 12 August 1945.[17][18] Her incomplete hulk was retained until September 1958, when she was broken up on the builder's ways.[11][19][A 4]

The ship's bell was cast, and now resides at Memorial Stadium at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It reads USS Illinois 1946. While University of Illinois records are unclear as to whether the bell was donated to it or specifically to the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) at the university,[20] an Associated Press article published in 1983 seems to indicate the latter.[21] According to the AP, the bell had previously resided in a Washington museum until finding its new home with the Fighting Illini football team in 1982;[21] since then, the bell is traditionally rung by NROTC members when the football team scores a touchdown or goal.[20]

Notes

- ↑ Although the Illinois was never commissioned by the U.S. Navy, and therefore did not officially receive the USS ship prefix, she is conventionally referred to as USS Illinois.

- ↑ This was not the first time that changes to the Iowa class had been proposed: at the time the battleships were cleared for construction some policymakers were not sold on the U.S. need for more battleships, and proposed turning the Iowa-class ships into aircraft carriers by retaining the hull design, but switching their decks to carry and handle aircraft (This had already been done on the battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga). The proposal was countered by Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations. "BB-61 Iowa-class Aviation Conversion". http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/bb-61-av.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ This bill was passed after the German invasion of France, which prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to demand that the US Congress fund a "Two Ocean Navy" to meet the threats posed by Hitler's Germany and Hirohito's Japan.

- ↑ Illinois was never considered for a rebuild of any type, while Kentucky was a candidate for a guided missile rebuild.

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Rogers, J. David. "Development of the World's Fastest Battleships" (PDF). http://web.mst.edu/~rogersda/american&military_history/World%27s%20Fastest%20Battleships.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ↑ Pike, John (2008). "BB-67 Montana Class". GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/bb-67.htm. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ↑ The work proceeded for several years, and significant excavation was carried out on the new approach channels; but the project was canceled after World War II. (Enlarging the Panama Canal, Alden P. Armagnac, CZ Brats)(Enlarging the Panama Canal for Bigger Battleships, notes from CZ Brats)

- ↑ Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-715-1.

- ↑ Staff (2 June 2006). "BB-67 Montana Class". GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/bb-67.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Minks, R. L. "MONTANA CLASS BATTLESHIPS END OF THE LINE". Sea Classics. September 2006. FindArticles.com. 2007-12-01.

- ↑ Naval Historical Center. Bureau of Ships' "Spring Styles" Book # 3 (1939-1944) – (Naval Historical Center Lot # S-511) – Battleship Preliminary Design Drawings. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The 10 Greatest Fighting Ships in Military History. The Discovery Channel. Web page: Top Ten Fighting Ships. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Johnston, Ian & McAuley, Rob (2002). The Battleships. London: Channel 4 Books (an imprint of Pan Macmillian, LTD). pp. 108–123. ISBN 0752261886.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Garzke; Dulin, Robert O. (1976). Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 137. ISBN 0870210998. OCLC 2414211.

- ↑ Adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index, each individual Iowa-class battleship would cost US $1.8 billion in 2008 dollars (Calculate Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 1665-2012).

- ↑ Staff (9 October 2007). "BB-61 Iowa-class Design". GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/bb-61-design.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "Iowa Class: Armor Protection". Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071224190717/http://www.battleship.org/html/Articles/IowaClass/Armor.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Beth Py-Lieberman. Any Bonds Today? Smithsonian. February 2002.

- ↑ "Calculate Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 1665-2012". http://www.austintxgensoc.org/calculatecpi.php.

- ↑ "Illinois". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. United States Navy. http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/i1/illinois.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "USS Illinois (BB 65)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy. http://www.nvr.navy.mil/nvrships/details/BB65.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Naval Institute Press. (December 1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. ISBN 0-87021-715-1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Chancellor Richard Herman. "Illinois On Our Watch". Public Affairs for the Office of the Chancellor and the University of Illinois Alumni Association. http://www.oc.uiuc.edu/OnOurWatch/infocus/102007.html. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Associated Press. "Rose Bell" rings loudly for Illinois. The Chronicle Telegram, Elyria, Ohio, Sunday, 30 October 1983. Page 31.

Bibliography

- Sumrall, Robert (1988). Iowa Class Battleships: Their Design, Weapons & Equipment. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870212982. OCLC 19282922.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Jr., Robert O. (1995). Battleships: United States Battleships 1935–1992. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557501742. OCLC 29387525.

- McCullough, David G. (1977). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671225634. OCLC 2695090.

- Barrett, John (1913). The Panama Canal, what it is, what it means. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Union. OCLC 244998670.

- This article includes text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

External links

|

||||||||||||||